MDU has completed a survey of workloads among OPD lawyers, core staffers, and social workers, and the responses paint a stark picture of an agency nearly overwhelmed by rising caseloads that management has been unable or unwilling to address.

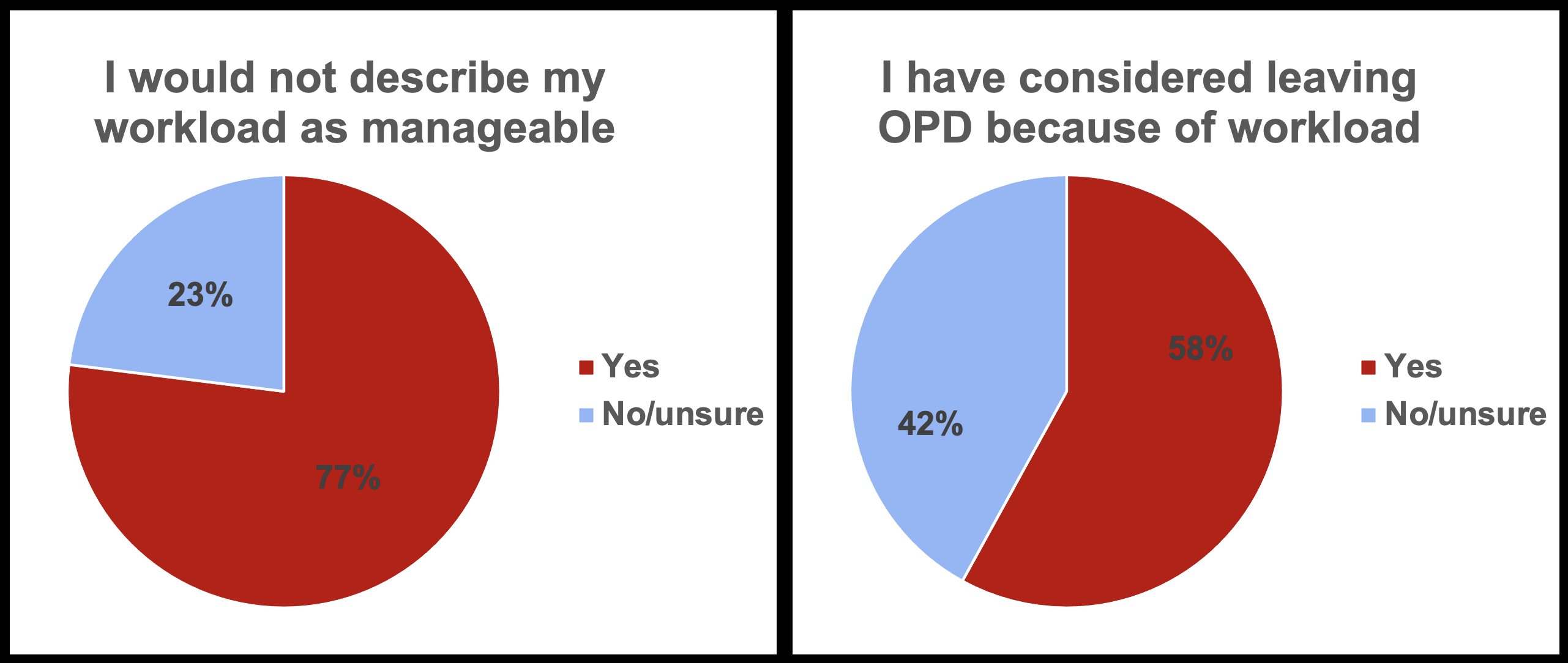

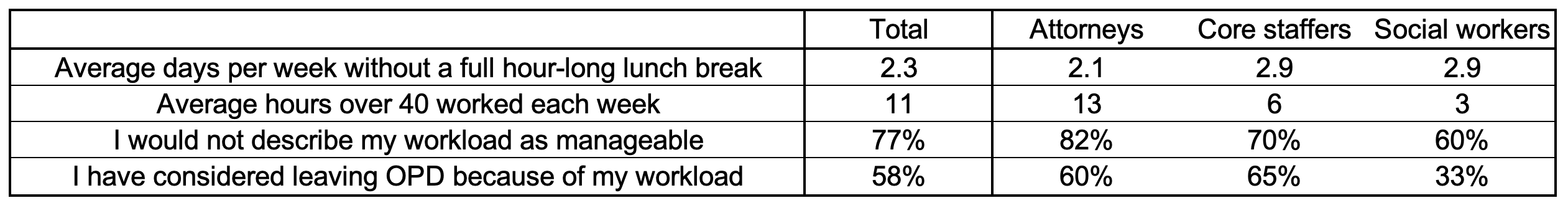

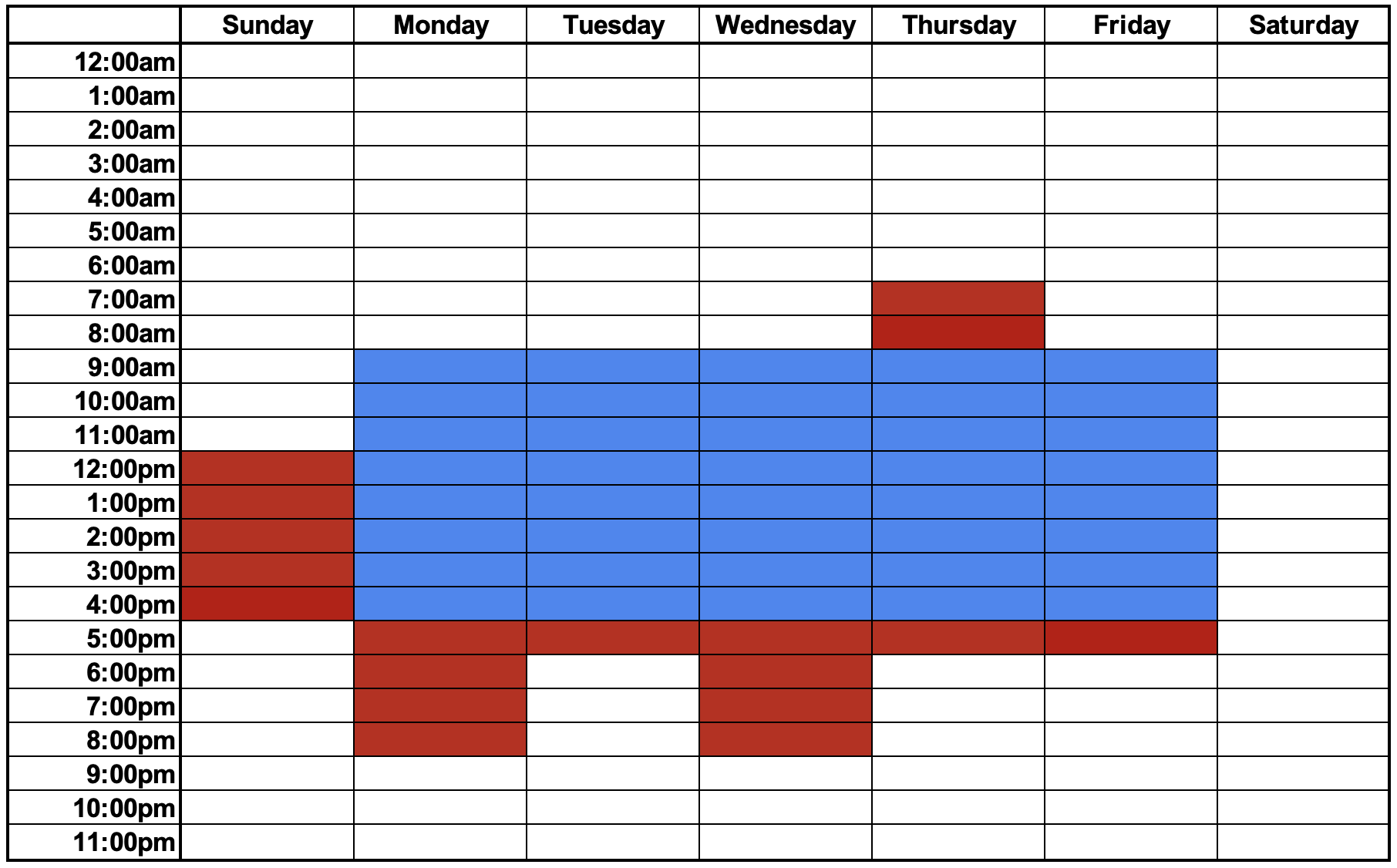

The average core staffer respondent works nearly a full day's worth of unpaid hours each week, and 65% of those core staffers have work responsibilities that are not included in their official job title. Half of social worker respondents said they were unable to meet their deadlines and duties within traditional work hours. And an estimate of caseload capacity using OPD's own analysis suggested that attorney respondents would need at least an extra 28 hours each week to give all of their cases the necessary time and attention. It is unsurprising, therefore, that 77% of all respondents said their workload was unmanageable, and that 58% had considered leaving OPD as a result.

The takeaway is clear: the status quo is bad for OPD workers and bad for OPD clients. Waiting for the problems to fix themselves hasn't worked. OPD workers need to take matters into their own hands. We need a collectively bargained contract with workload standards that keep OPD employees from burning out and ensure that OPD clients get the representation they deserve.

Take action today:

- Sign the MDU's petition calling on the Maryland Legislature to give OPD workers collective bargaining rights! You don't need to be a member of the MDU to sign the petition – you just need to support equal rights for OPD workers and better representation for OPD clients.

- Share the petition with your coworkers and encourage them to sign! Send them the link – bit.ly/MDUpetition – or email [email protected] for a paper copy of the petition. Anyone who collects ten signatures gets a SWEET prize, and the person who collects the most gets a GRAND PRIZE!

- Join the MDU! We're strongest when we stand together. If we want OPD to be an agency we can be proud of, we need to organize.

Read on for a detailed breakdown of the survey results. And if you didn't take the survey but want to make sure your voice is heard on the workload crisis at OPD, email [email protected].

* * *

Overall conclusions

Of the respondents to the survey, 75% were lawyers, 17% were core staffers, and 9% were social workers. This roughly matched the breakdown of employees agency-wide (58% lawyers, 34% core staffers, and 4% social workers). Several questions were asked of everyone who took the survey, regardless of job type.

* * *

Attorneys

Different questions were asked of attorneys based on their role within the agency. The attorneys who took the survey and work in the divisions focused on a specific subject matter – Appellate, Forensics, Mental Health, Parental Defense, and Post-Conviction – were asked questions about the type of workload specific to their division. The number of attorneys in those divisions is small enough that their responses can't be analyzed from a quantitative perspective, though their responses to several qualitative questions are included below.

Attorneys working in the twelve geographic districts were asked questions about their caseload in both District and Circuit Court. For attorneys working in District Court, the survey asked them to estimate how many traffic and criminal cases they have in an average week. And for attorneys working in Circuit Court, the survey asked how many cases they currently have in several categories of escalating severity:

- Post-trial representation (such as modifications or sentence reviews)

- VOPs

- Jury-trial prayers and other misdemeanor jury trials

- Cases with a maximum sentence on the most serious count of less than twenty years

- Cases with a maximum sentence on the most serious count of more than twenty years but not life

- Cases with a maximum sentence on the most serious count of life

We used those caseload numbers in conjunction with OPD's own caseload study from 2005, which established baseline amounts of time an attorney should spend on different types of cases in order to provide effective representation, and came up with a rough estimate of the amount of time each respondent "should" be spending on their assigned cases. There are several reasons to think this is an under-estimate of the actual amount of time needed for vigorous, constitutionally effective representation:

- The conclusions of the 2005 study are outdated in a number of respects. In particular, the rapid growth in the use of body cameras, dashboard cameras, and other forms of recording since 2005 means that attorneys across the agency have to spend large amounts of time reviewing large amounts of footage on many of their cases. Of the attorney respondents, 99% reported that cases in their jurisdiction generally or sometimes have body camera footage, and they reported an average of seven hours each week spent watching that footage. Body cameras were not nearly so widespread in 2005, meaning that this demand on attorneys' time was not factored into the recommended baselines.

- Moreover, the recommendations of the 2005 report were seen by many frontline OPD attorneys as insufficient. Certain adjustments and normative decisions about how much work a case "should" require meant that the 2005 recommendations were higher across the board than the American Bar Association's recommendations for public defense caseloads. Even in 2005, these recommendations were better understood as minimum requirements for competency, not sufficient time for vigorous and assertive representation.

- The 2005 study also predated the change in state law that resulted in OPD taking responsibility for representation at bail reviews. On average, respondents estimated that they acted as the "bail review" attorney three times each month and represented an average of seven clients on each of those days. That time was not factored into OPD's 2005 study or our estimate derived from the study.

- Finally, on a technical note, the nature of MDU's survey is that we collected information about Circuit Court caseloads at a point in time, rather than spread across a whole year, while the 2005 study's recommendations are given on a yearly basis. As such, our survey results give the amount of time an attorney would need in a year if they didn't add any more cases after taking the survey (which obviously will not be the case for almost any respondent). While taking yearly case turnover into account was unfortunately beyond the capacity of this survey, it would certainly lead to significantly more dire results.

But even with all of those caveats, the average attorney survey respondent has a caseload that would require them to work 170% of their available yearly capacity, or the equivalent of 68 hours per week. Once one takes into account all the reasons to think that this is an underestimate of the actual time required, it is likely that attorneys would have to work twice as many hours as are in a normal workday to represent our clients in the manner that they deserve and are guaranteed by the Constitution.

A representation of a standard forty-hour workweek (in blue) and one way of reaching sixty-eight hours (in red).

The impact of those impossible demands is visible in the responses to the survey's more open-ended questions. OPD's frontline attorneys are overwhelmed and suffering, but above all else, they are concerned about the impact of OPD's swelling caseloads on our clients.

"It’s impossible for me to give effective assistance for all of my clients, given the amount of time it takes to prep a case well. Even simple drug cases can have a dozen hours of body worn camera, CCTV, and/or dash cam footage." Circuit Court Attorney, District 1 (Baltimore City).

"I have barely enough time to speak with each of the clients I represent during the week, and jail clients are even tougher to dedicate the amount of time to that I should. Since I am in the courtroom so frequently, finding windows of time to do all of the out-of-court tasks that I need to is nearly impossible during the work week as currently structured." District/Circuit Court attorney, District 5 (Prince George's County).

"I cannot put the amount of time each client deserves into their cases. I always have to triage to focus on the cases where I have the greatest chance of beating charges, but, when it comes down to it, whether we go to trial is up to the client, and I end up going to trial on cases to which I could not dedicate sufficient time. There are so many more cases I would take to trial if I had enough time to really master the details of the case." District Court attorney, District 7 (Anne Arundel County).

"I used to have time for a social life. Now I'm lucky if I get to see my relatives once a month. I no longer have time or energy for exercise, and most nights are sleepless." Circuit Court attorney, District 8 (Baltimore County).

Attorneys also recognized that solving the workload problem means organizing and fighting for change across the agency, not just among attorneys.

"My workload has increased substantially over the last three years due to the removal of full-time, paid law clerks. . . . I can't manage all the tasks outside my job description that I have to do." Circuit Court attorney, District 1 (Baltimore City).

"My workload is unmanageable not just because of my cases, but because we also have to do all our own administrative work and investigation. If we had more support staff it would probably be manageable." District/Circuit Court attorney, District 4 (Southern Maryland).

"The caseload would be challenging under any circumstances, but the administrative burden during COVID has made it much harder. It’s one thing to have too many clients, but too many clients plus no charging documents, having to identify clients who fall through the cracks after qualification, having no good system to avoid double booking between District and Circuit court, and having eDefender be too slow to be of much practical use during the work day – it does not leave sufficient time to represent every client as well as possible. And the problem builds on itself as good, experienced attorneys leave and their caseloads are reassigned, further straining everyone else, and leading to more departures." District/Circuit Court attorney, District 5 (Prince George's County).

* * *

Core Staffers

Unlike with attorneys, we weren't able to come up with a quantitative estimate of what the workload of a core staffer "should" be, because OPD management has never bothered to analyze or study core staffer workloads. Every OPD employee knows that the work done by our core staffers is critical to our effective representation of our clients, and that pervasive under-resourcing of core staffers is taking a toll on the quality of that representation. But OPD management has never tried to create workload standards for core staffers, or even ask them in a systematic way about their workload. That's shameful, and it's one of the things MDU wanted to address in some small way through this survey.

The job titles of core staffer survey respondents included Admin Aide, Intake Specialist, Office Clerk, Office Secretary, and Paralegal. However, one of the primary takeaways of the survey was that those job titles do not correspond to the wide variety of tasks core staffers are called on to perform at the agency. More than 70% of respondents felt that their job title did not accurately reflect the work they do for OPD, and on average, they estimated that 42% of their time at work was spent on tasks that fall outside of their job title, including:

"Training incoming staff."

"Preparing and filing motions for attorneys and performing legal research."

"Serving as the Spanish interpreter for the entire office and working with attorneys from beginning to end on any case with a Spanish client."

"Reviewing cell phone cases for GPS mapping and cellphone extraction."

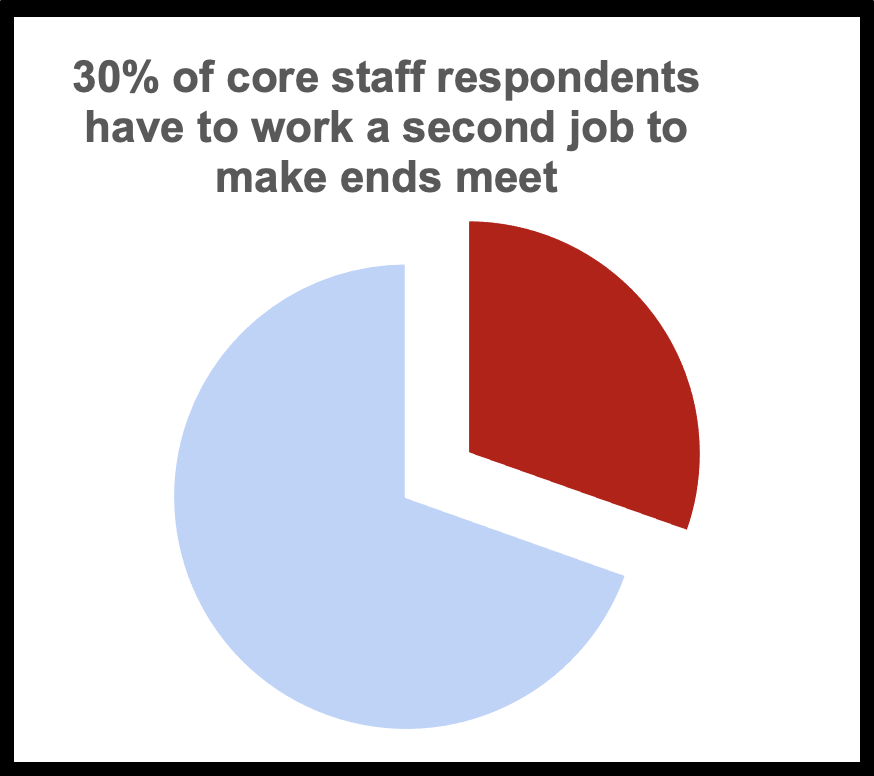

But without those added responsibilities included in their job title, core staffers are not compensated for their expertise and experience but paid as if they are only performing their official duties.

This is part of a larger trend of OPD requiring core staffers to perform unpaid work. Sixty-five percent of respondents reported having to work more than the standard 40 hours per week, at an average of more than eleven extra hours each week. And, unsurprisingly but frustratingly, none of the respondents are paid overtime or even paid at all for those additional hours.

All this contributes to OPD's outrageous underpayment of core staff. Previous MDU analysis of public salary information found that core staff salaries at OPD start low and barely increase over time, meaning that even a core staffer with decades of service at OPD isn't making enough money to support a family. And 30% of respondents to this survey reported having to work a second job to make ends meet. One full-time job should be enough. It is reprehensible that any OPD employee, especially the core staffers who put in so much of the labor that keeps our agency running and gets our clients the representation they are guaranteed by the Constitution, are not paid enough to make ends meet.

It was outside the scope of this survey to develop a quantitative estimate of how many additional core staffers are needed at OPD if we want them to be able to do their jobs well in a single forty-hour week. But what the results of the survey clearly demonstrate is that OPD's workload crisis is not limited to attorneys but encompasses core staffers too. OPD management needs to take core staff responsibilities seriously and recognize them for what they are: not a peripheral or secondary concern, but a key part of our representation of our indigent clients.

* * *

Social workers

Finally, a number of social workers completed the survey, but with fewer than 30 social workers for the entire agency, we were not able to analyze social worker responses with a significant level of quantitative detail. However, even taken on their face, the responses are worrying. Half of social worker respondents said that they are unable to meet their work responsibilities within normal working hours, and one quarter felt that caseload pressures were impacting the quality of their work.

Several themes are apparent in the qualitative responses given by social workers to this survey (and to a second, social worker-only survey disseminated earlier in the year). Respondents felt that more social workers were needed across the agency, but that the trend of using non-PIN social workers – employees funded by time-limited grants rather than permanent, state positions – to temporarily plug those holes was problematic.

"There are so many cases that need social workers that do not get them because our caseloads are too high."

"Panel social workers and grant-funded social workers are not an adequate solution to social work caseloads. We need to invest in more full-time social workers and the tools to help us do our jobs better."

"I wish I could take more cases but each case is so complex and requires so many hours.

On the whole, social worker responses generally aligned with those given by attorneys and core staffers, but to a somewhat lesser degree. Of the three job classes, social worker respondents had the lowest rate of reporting an unmanageable workload (50%) and of considering leaving OPD because of their workload (33%). If anything, however, this should serve to highlight the dire nature of the agency's workload crisis – that "only" one-half of a group of employees reporting that their workload is too demanding can be considered a good sign in comparison to other groups of employees in even worse positions.

* * *

In conclusion, frontline OPD workers across the entire agency are in crisis. Even with workers putting in dozens of extra, unpaid hours each week, workloads are so high that OPD is falling short in its mandate to provide effective, vigorous representation of our clients. We need change, and we need it now. OPD management has been unable or unwilling to do what it takes to solve the problem. It's time for us to take matters into our own hands. Sign the MDU's petition for collective bargaining rights, share the petition with your coworkers, and join the MDU today.